Alyx Vance and the Infinite Value of Empathy

Spoilers for a video-game franchise called Half-Life abound

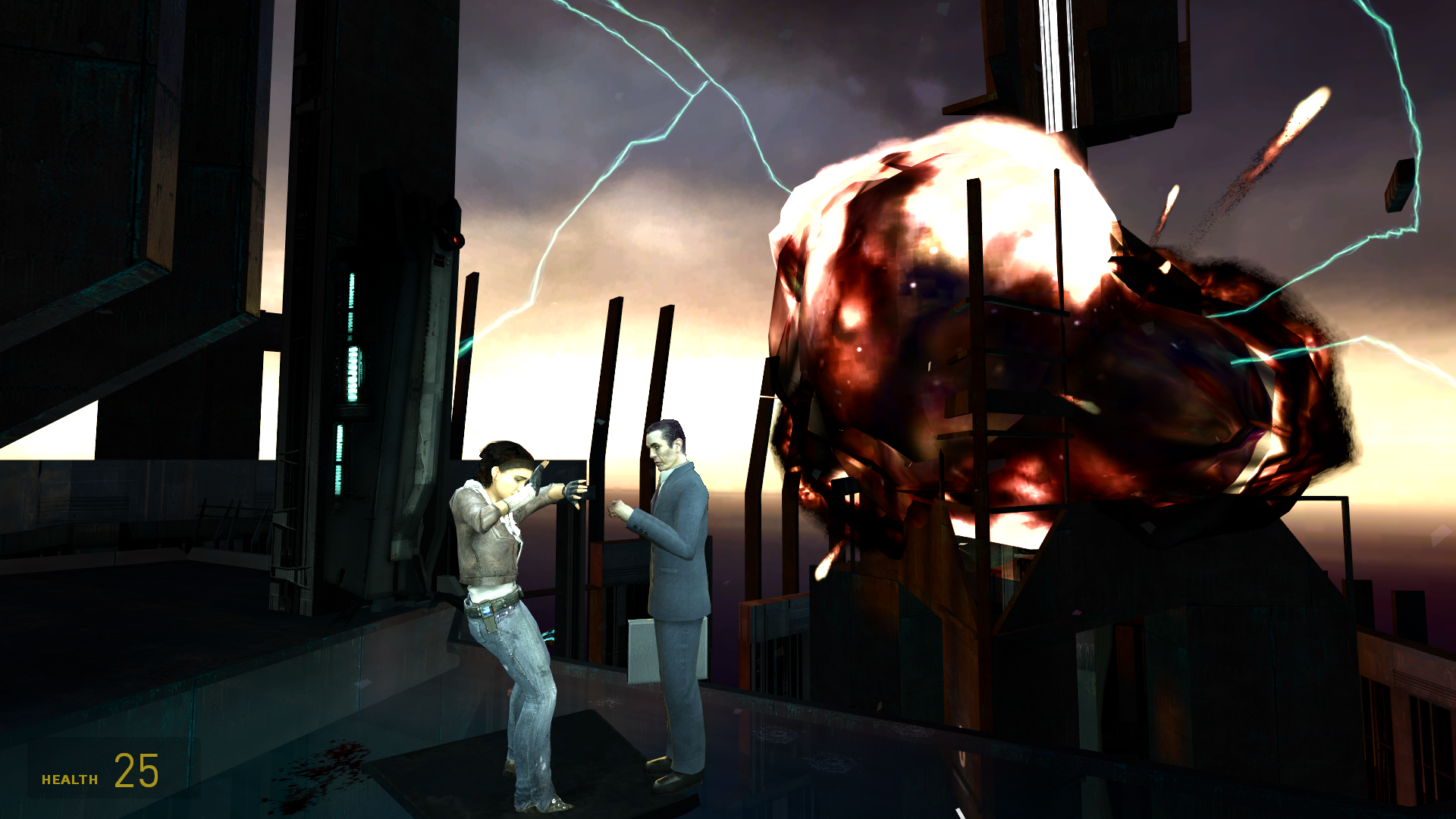

In our first encounter with the enemy, we get our asses kicked. Unarmed and vulnerable without the protective layers of the HEV suit, a small gang of metrocops are able to ambush and beat us to the floor. Given our last confrontation, a decade or two earlier but a blink of the eye for us, was with a giant, bilious baby monster from another dimension capable of firing electricity from its fingertips, this is a touch embarrassing. It’s a humbling reminder that we don’t know this strange new world. We’re an outsider here, and a very vulnerable one at that.

It might have ended there – our only achievement the meagre ration reward these thugs would have earned for turning over an enemy of the state – had it not been for a young woman’s timely intervention. As we lay dazed on our backs, we heard her do what we couldn’t, saving us from the Combine’s cruel punishments. But as our senses returned and the woman entered our vision, far from appearing anxious or perturbed, she smiled warmly, seemingly pleased to see us and acting as if violent contact with the Combine’s enforcers was just par for the course.

She introduced herself with a winking reference: “Doctor Freeman, I presume?”

I don’t know about you, but up until that point, no one had ever looked at me like that in a game before. Like, really looked at me, as if I was right there in the world as a living, breathing soul, consciously acknowledged and given substance by a computer generated entity. And it was then that I realised Valve’s ambition to create lifelike, realistic characters had succeeded in ways I hadn’t anticipated, although I couldn’t name them exactly. Further, I didn’t realise the extent of the spell that had been cast. Because at 14, I wasn’t too troubled by questions of what it meant to be immersed in a video-game narrative, or what populating such worlds with lifelike characters entailed. I just cared that it looked good and felt good and can I shoot some baddies please.

My perspective’s changed a bit. I do still want to shoot baddies, but I care about other things, too. I’ve developed some thoughts on narrative, on games, and what happens when the two come together. So, I think I can be a bit more specific about the aforementioned successes now. I can’t guarantee that I’ll do so with any success myself, but maybe sometime in the future I’ll be in a position to more successfully elaborate on those successes than I am today. As it is, I’ll give it a shot. Let me know if I miss.

The Look. A triumph of several disciplines working to achieve that perfect moment, it serves as the gateway into what Half-Life 2 is all about. It’s that look that sets the whole thing in motion – the moment upon which all other moments are built, from Half-Life 2 to the tragic, heart-rending conclusion of Episode Two. It’s the moment in which empathy is first created, and the work of the ensuing story is a constant expansion of that limitless, empathetic frontier.

Roger Ebert once called movies “machines for empathy”, which, however bandied about that statement has since become, is in essence true. And it is true of so many great stories, be that in film, prose, or – in spite of Ebert’s antipathy – games. We intuitively know this, understanding that one of the fundamentals of storytelling is to immerse us in the thoughts and feelings of others, to present us with the lived experience of the other and ask us to empathise with it. But how to do that in a game, when assuming a role, playing in a created space, and acting with agency presents new obstacles and challenges for storytellers? I write retroactively, of course, because the medium has answered this in many different ways over the last sixteen years and expanded in surprising, even revelatory, directions (Valve know this; see the absorption of the Firewatch team).

Back in 2004, though, the situation was different, and for Half-Life 2 in particular, with its silent, ostensibly personality-free protagonist, the answers were also quite different.

“I’m Alyx Vance," said Valve’s answer. “My father worked with you, back at Black Mesa? I’m sure you don’t remember me though,” our new friend demurred. In truth, no, we didn’t. But from this moment on, we’d never, ever forget Alyx Vance. She became the unexpected heart of the Half-Life 2 era. A character whose warmth, wit, tenacity, and intelligence was everything the series’ famous avatar, Gordon Freeman, was not. Or rather could not be.

Alyx was a child of this new world. A little girl during the Black Mesa Incident, Alyx's adult life had only ever known Combine subjugation. And yet here she was, smiling, cracking awkward jokes, and enjoying the company of friends and allies. She was imbued with an innate sense of optimism in a world determined to grind the human spirit to ash – a spark of hope so bright, it would ultimately light the way to the very tip of the Citadel, overthrow Breen’s sham regime, and blind the Combine’s portal network.

And from there Alyx Vance went on to become one of the greatest heroines in video-game history. Independent, strong-willed, and smart, effortlessly transcending the low standards of a medium that has objectified, degraded, and insulted women for most of its history (this didn’t stop a number of publications listing her as “hottest" this or “sexiest" that, intent on viewing her through their broken lens. We don’t have to deny Alyx’s evident sexuality, but it does mean discussing it in terms of hers, not ours). Alyx’s ethnicity is vital, too. A multiracial female protagonist in this medium is tragically rare – an important piece of representation that often goes overlooked. That the first Half-Life game in many, many years - a flagship VR title - is about to launch with a multiracial female protagonist and her African-American physicist father is nothing short of a very big deal.

Valve knew this in 2005, too. Is it any wonder the first word out their mouth when they announced the episodic trilogy was “Alyx”? Indeed, the general arc of Half-Life’s development over the past sixteen years can be mapped along the lines of Alyx’s increasing importance. Just ask the G-Man. That dude knows what's up.

All of which is to state a pretty plain fact: Alyx Vance was, and is, important.

Now, in our increasingly fraught, anxious 2020, we're just one week away from the first Half-Life game in a long, long time. That game is called Alyx, and it's not just a prequel; it's billed as the next chapter in the Half-Life saga. But before we look ahead to that latest instalment, it’s worth looking back at Half-Life 2 and its initial sequels, to better understand how that arc took shape – and why it’s so important.

I recently spoke on Twitter about what I thought HL2 was really about, what I thought it was trying to say, and why I think it has the strongest conclusion in the series. As I think I’ve said somewhere before, I've never really considered HL2’s story to be anything more than a really well-written piece of science-fiction. It doesn’t carve out new ground in the dystopian alien invasion sub-genre, nor does it have anything fresh to say about, I don’t know, oppression, or the nature of totalitarian systems (nor, I should stress, does it have to). But HL2 is not without subtext, at least not to me. It's just that HL2 has more to say about that medium where the really-written story is rare than the content of the story itself.

To recap (and elaborate more freely and at length—sorry!): the argument I posited was that HL2 is about free will within a game – about what it is to become involved in a world, immersed in a setting, and absorbed by its narrative. HL2 knew that ace storytelling wasn’t a hallmark of the medium and resolved to change it, and in pursuing that goal it couldn’t help but integrate what that meant with everything else it was doing in the process, be that its realistic characters or its groundbreaking physics engine. I'm pretty sure, for instance, Half-Life 2 was the first game to ever convey mood and feeling through a character's mannerisms as much as dialogue effectively. Marc Laidlaw, the series' previous lead writer, once cited Breen's eye roll at Mossman's entreaty in the Citadel as one of his favourite moments, as Breen's gesture was clearly intended for the player alone. You hadn't seen that before.

It wasn’t so much about the story it was telling, but the manner in which that story was told. Because before you could craft a narrative filled with meaning and import, you needed to create characters players could believe in. You needed to devise a mechanism for narrative delivery that was different to other narrative-driven games. So, with the original Half-Life as their base, that's just what Valve did.

HL2 is a very linear experience. It’s a game of meticulously crafted moments, scenes, and set-pieces, made at a time when the game industry was becoming fixated on open world settings, making non-linear gameplay near ubiquitous in first person shooters. HL2, in appearance, was still indebted to the era from whence its progenitor came. Some saw that as a weakness, but that seems to me a preference thing rather than a decent critical perspective. The point is, anachronistic or not, HL2 was an on-the-rails shooter with a succession of scripted sequences. You moved from A to B along a predetermined path, and other than the manner in which you chose to engage each sequence, you didn’t have much, if any, freedom to roam or pick alternate routes.

But that’s not to say the game was without its own sense of freedom. Over the next however many (too many) words, I'll try and describe what that freedom feels like to me now, and why in the end it all comes down to one Alyx Vance.

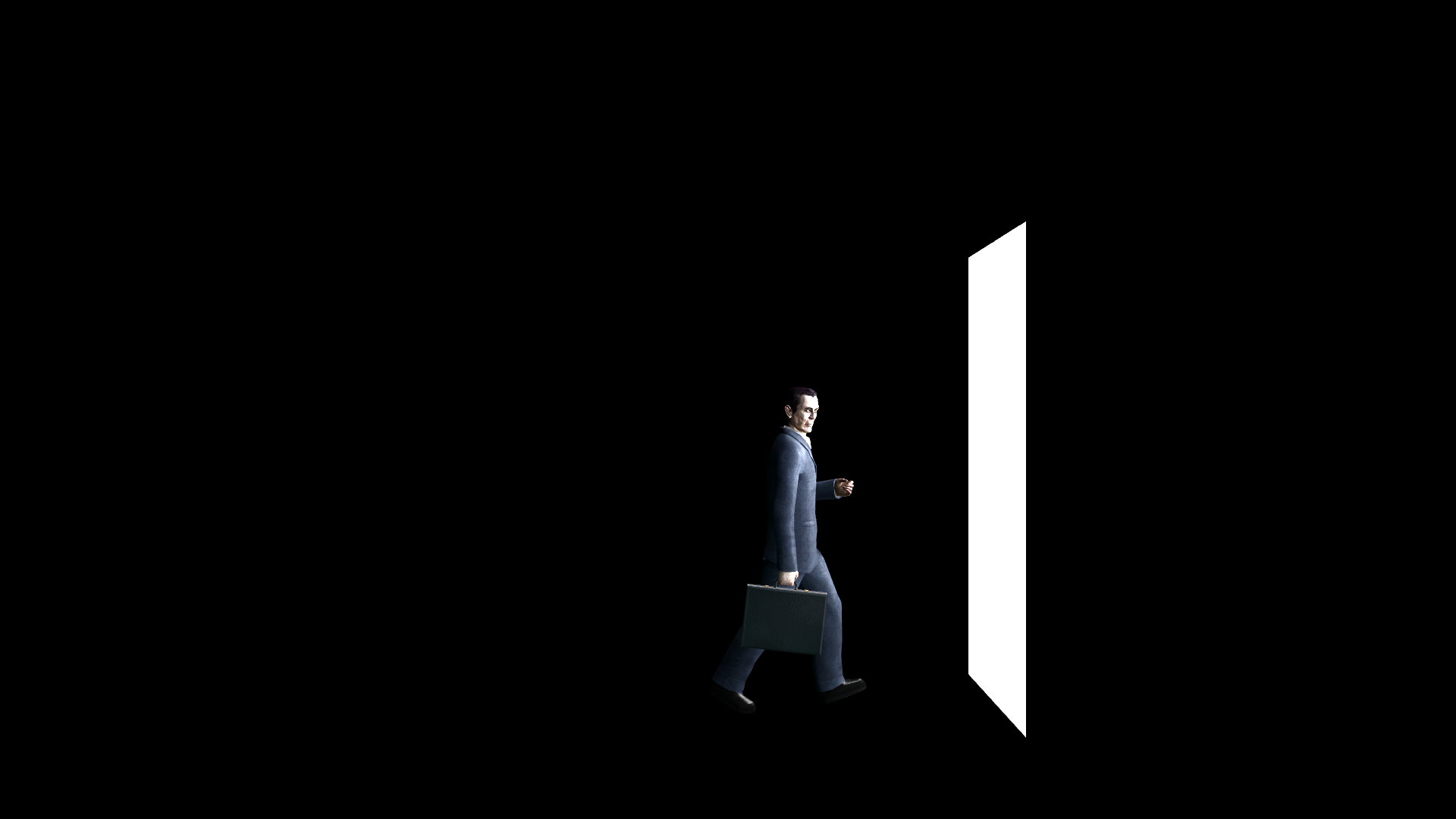

The game begins with Gordon Freeman, our in-game avatar, being dropped into City 17 by the G-Man, our sinister employer of unknown origin. Quite what he’s hired us for is a mystery, but we're pretty sure our doctorate in theoretical physics has very little to do with it. We're this guy’s pawn and he has a purpose for us. He doesn’t say what that purpose is, he simply expects us to find our own way towards what he wants.

The moment we open our eyes for the first time in nearly two decades, we find ourselves a powerless citizen in a dystopian alien police state. That’s troubling for many reasons, but the worst of them might be the niggling feeling that we're responsible for it. There’s a link between the present and Black Mesa, but its only shape in that moment is guilt.

The atmosphere of oppression is palpable. Destitute citizens in identical blue uniforms wander the cold streets, their every movement surveilled by probing Combine scanners and metrocops with tight grips on their batons. The water’s drugged, intended to distort the memory and sow confusion. Memory - a component of our humanity the Combine want isolated and removed. “Reminder: memory replacement is the first step towards rank privileges,” the clinical voice of the Combine Overwatch declares in one of her frequent announcements. To forget is to ascend.

It is a city without respite. Giant monitors bearing the face of Doctor Breen adorn the walls, issuing a relentless, droning assault in the form of tortured homilies and cold, unfeeling rationalisations for the Combine's tyranny. It transpires Breen is the man who brokered a deal with the Combine to spare humanity, elevating him to a position of questionable power – a Marshal Pétain for this occupied world. It’s from these monitors he instructs humanity to surrender their minds, their bodies, and to be willing collaborators in their own misery. To eat shit and pretend it’s a gourmet meal. The face of the Combine occupation: a condescending old white dude. Somehow, that’s not terribly surprising.

Without direction, we’re simply immersed in this world and invited to put the pieces together ourselves. There’s no prologue to catch us up on what’s happened. No tidy explanation. We just have to experience it, and Valve’s Source Engine is built for the task. Every step is a fresh discovery, and every new face expects us to know more than we do.

A series of fortuitous coincidences ensue, putting us back in contact with old friends from Black Mesa. They too feel no small amount of responsibility for humanity’s emaciated condition, and are determined to right Black Mesa’s wrongs. It’s unsettling that they almost seem to have been expecting us, but we shelve that for the moment, unsure what, if anything, it means.

It’s here we meet Alyx Vance, the young woman who saves us from capture. She is a face of hope and optimism, symbolising a chance for renewal. HL2 wants us to care about Alyx and it takes some big steps to encourage us to do so. She certainly cares about us. She cares about a lot of things, actually, and she's going to invite us to share them. And who is this woman, who knows so much about us, and treats us with a kind of knowing, winking reverence? Well, like us, Alyx is both a scientist and a freedom fighter, although her aptitude for the former far outstrips ours, it seems. She's inspired by her father's idealism and committed to resisting Combine rule, closely involved in helping citizens escape City 17 by way of an underground railroad. Alyx views our arrival as portentous, remarking that it's "funny" we'd turned up on this particular day - the day Kleiner's teleporter was finally ready to start transporting people out of the city much more quickly. But it's a different kind of expectation to the one expressed by the others, and it brings us closer to her.

And, well, she does seem to like us. Quite a lot, actually.

With introductions old and new made, the board is set and a journey into this oppressive world begins in earnest. The narrative settles into a struggle between a cold, mechanistic science and a life-affirming, empathetic one. And there’s that word again.

For the first half of the game our involvement is one of accidental chaos. Wherever we go, trouble follows. The Combine pursues us through the canals, bringing down destruction upon the underground railroad. Our arrival at Black Mesa East – a Resistance haven – is swiftly followed by a Combine strike, resulting in the capture of Alyx’s father, Eli Vance, and researcher Judith Mossman, both key figures in the Lambda Resistance. Once our first calamitous day on this scarred, bleak Earth has concluded, we're compelled to undo our recent fuck-up: infiltrating the Combine’s processing plant, Nova Prospekt, and liberating Eli and Mossman.

It’s important we do this not solely because Eli Vance is pivotal to the Resistance, but because it matters to Alyx. Prior to his capture, Eli explained that Alyx’s mother, Azian, was lost, sadly noting that Alyx and a family picture was all he managed to carry out of Black Mesa. There’s more to that story than we could possibly know, even if we suspect Eli carries more secrets than he lets on. But right now, it’s a revealing window into Alyx’s life. Black Mesa took something precious from her, and we understand that her relationship with her father is more important because of it. He's all the family she has left.

As with Alyx, Valve very much wishes for us to like Eli Vance. It's hard not to. He’s a genial, kind, welcoming figure, whose love for his daughter is boundless. His priorities are split right down the middle: rescuing humanity from his past mistakes and keeping Alyx safe from them. It's no easy task when Alyx herself is set on helping him do it, so there’s tension there, but Eli carries it well. As a player, we can’t help but take note of the relationship between father and daughter and be moved by it. Eli gently teases Alyx in front of us, shows concern for her well-being, and encourages her as both a scientist and fighter. He’s proud of her, and she of him, and whilst that may seem like a pretty basic setup for two characters, at the time I don’t think it’d ever been done with such sophistication, elegance, and genuine human warmth.

And what was so special is that they were performing the relationship not just in front of us, but in response to us. We were in the room, and that mattered to how they interacted around us. It was a revelation, and to this day it is still a pleasure to descend that elevator in Black Mesa East, to be greeted by Eli's encouraging words to his vortigaunt lab assistant.

We’d been initiated into a close family bond, which included Isaac Kleiner, Barney, and, to a lesser extent, Judith Mossman. We wanted to be a part of it. “It’s not Black Mesa, but it’s served us well enough." Perhaps, with time, it would serve us, too.

So far, aside from the character dynamics, HL2 has prioritised environmental storytelling over expository dialogue. We learn of humanity’s downfall and Breen’s ascendance by way of newspaper clippings on a cork board. The Combine? We have only a vague understanding of what they are; our response is almost entirely emotional, having witnessed a slew of wicked atrocities, from horrific bio-warfare to nothing short of genocide. Their malevolent organisation is opaque, and we understand them best when experiencing them through characters who have some pretty strong feelings about 'em.

Now, journeying up a barren coastline on our second day, we see with our own eyes the kind of impact they've had on the landscape. A depleted, inhospitable ocean; civilisation routed, with only the ghosts of a mostly forgotten past littering the roads and cliffs in the shape of abandoned villages and rusting car husks. It is a vision of the future, in which all that’s left of Earth is a remote outpost on the fringes of the Combine’s dominion, its remnants deprived of meaning, for there is no human being left with the faculties to remember. And that place we’re heading, this Nova Prospekt – we will learn that’s where memory is exorcised.

We don’t quite know why this nightmare came to be, but we know how: Black Mesa.

We didn’t intend to, but we helped unleash this.

We know we were manipulated somehow, but it doesn’t matter. We pushed the crystal into the beam. It’s on us.

Our first intake of breath in this oppressive world was as a pawn, but that seems distant now.

We need to set things right.

We need to help these people we've come to care about.

We need to unleash revolution.

And so once we reach Nova Prospekt with an army of antlions at our command, we experience our first real taste of power and agency. It's interesting that it arrives just over halfway through the game, when players reasonably expect to wield it the second they click 'New Game'. But it’s true that up until now, our actions have been in response to events beyond our control, and those actions have had unintended consequences. Our role has been a reactive one. Rescuing Eli Vance and Judith Mossman is a correction of a recent folly, not a decisive change in the status quo.

Nonetheless, the Combine has pursued us from the moment we stepped foot in this world, but now we're going after them. It doesn’t pan out: before we can rescue Eli Vance a traitor is revealed, threatening to derail our efforts. Judith Mossman is a double agent, spying on the Resistance on Breen’s behalf. It’s Alyx who discovers this, and the betrayal cuts deep. On the one hand, she uses it to justify her personal antipathy towards Mossman, but on the other, Eli and Mossman clearly had a romantic relationship, and she knows it’s going to break her father’s heart. Briefly, Mossman refers to us as "someone's puppet", but the remark is unexplained, and the argument moves on. The G-Man briefly flickers in our consciousness.

Actually, I’d like to take a quick opportunity to talk about Mossman here, mostly because she’s HL2’s most underserved character, despite having what I would argue is the strongest dramatic arc. I know that sounds contradictory, but it's true. Unlike the rest of the cast, Mossman’s allegiances are conflicted, and she’s torn between Breen’s persuasive rhetoric, the Resistance’s scientific idealism, and her love for Eli. I still find it pretty powerful when she attempts to convince Breen of the importance of keeping Eli alive. Unconvinced, Breen proceeds to condescend to her about her “feelings” impairing her judgement. His willingness to talk right over her reveals the character’s grotesque misogyny, and Mossman’s defeated body language at the end of the scene absolutely tells us she’s experienced this bullshit so many times. "So sorry, Judith," says Breen, dry and mocking. "I'm all out of time."

I think there’s so much potential there, but the game never really explores it. Mossman’s relationship with Eli is mostly used to generate conflict with Alyx, relying on a rather trite stepmom conflict that the game is genuinely above. Nevertheless, we experience the betrayal through Alyx – we don’t feel betrayed because we’re still on the periphery of this thing, but we understand the implications on Alyx’s behalf. And that’s so important.

In the midst of our escape plan Mossman gets the better of us, and transports herself and Eli to the Citadel. Desperate, we flee via the Combine’s new teleporter, Nova Prospekt crumbling around us. We arrive back in Kleiner's laboratory just as the facility is blown away. Inexplicably, a week has passed during our seemingly instantaneous passage. And it was not without incident.

Our assault on Nova Prospekt has triggered revolution, and City 17’s citizens are now engaged in open war with their oppressors. We didn’t intend to signal it, not specifically – when do we ever? - but our actions were interpreted as such nonetheless, and a desperate battle for liberation is now underway. We wanted to engineer insurrection, now it’s here. We've spent long enough in this world now to understand the desire for revolutionary change. We despise the Combine and their human puppet and we're determined to topple them. That HL2 is told in a kind of real time without interruption is part of the spell it’s able to weave, by taking huge steps to immerse us in its world and elicit the precise emotions it wants us too.

In a way, we've forgotten about the G-Man and his mysterious goals. Who he is and what he wants matters less as the game progresses, receding into that first day in which we were dropped into this nightmare. Yes, we can spy him from afar here and there along the road, but there’s more a sense of that being a fun cameo that’s part of the Half-Life ethos than anything meaningful. It’s a “G-Man sighting”, not a plot point.

The only exceptions are when he’s spied conversing separately with a vortigaunt and, later, Odessa Cubbage. We’re reminded of the beginning, and our suspicion that the Resistance expected our arrival. What’s going on here? It induces feelings of alienation, subtly introducing a degree of separation between us and our friends. There's something they know about our condition that we don't, and why they'd keep that from us is a mystery that is left unsolved. What bargain did they strike that necessitated silence? And crucially, does Alyx know? It's unlikely, but doubt is aggressive once it has taken root.

We haven’t much time to think about it. Valve continue to push us farther down the road, and soon enough it’s ushered into the background, or at the very most filed as another fun G-Man sighting. That silly rogue. We’re again immersed in the unfolding drama, a drama to which, increasingly, we feel like we belong. We’re so fixed on our immediate goal of overthrowing Breen – a goal that we feel we have organically created through our own actions – that we forget the G-Man controls us, our every step. That we’re just a pawn.

But we are not a pawn. Our entire being is directed at resisting Combine rule and breaking humanity's shackles. We are, are we not, "The One Free Man"? What role does the G-Man have in this world, anyway? He seems so removed from events as they stand it's like he's just some phantom we half-dreamed in the chaos of the Nihilanth's demise, all those years ago.

The game is so good at convincing us of our agency in this world that there’s a potent sense of feeling like you’re truly driving the action now. Simply put, we’re at the point in the game where the effort to make us care about this world and its inhabitants has succeeded. We do.

As we fight alongside Alyx and Barney and push the Combine farther and farther back towards the Citadel (a very nice metaphor, given it’s where they came from), we're encouraged to feel like we're in the thick of it. A force of power and agency, capable of engineering events, not merely reacting to them. It’s a far cry from bumbling through the canals. At one point, Doctor Breen addresses us directly, berating us for our actions. It’s the first time he’s spoken to us, which solidifies this idea that we’re exercising our maximum agency as a player now. Because as we know from The Look, when a character speaks to us in this game, they are truly speaking to us.

The war’s going in our favour until Alyx is captured. Our ally - our friend - is taken. To the Citadel – no doubt about that. Now we have an even stronger reason for driving forward. There’s no one ordering us to rescue Alyx, but we want to - need to - and it compels us forward. Striders fall, buildings are razed, and eventually, with a little help from D0g, the Citadel’s outer-wall is breached.

As a lone knight we infiltrate the spire, Breen addressing us every step of the way. He starts from a place of smug distance, swiftly pivoting to frustration and concern the closer we get to him. You’re having an impact, making a difference. The character is angered by us – better, he’s afraid of us. It’s not just because we might kill him, but because our destructive trajectory threatens the precarious position he’s built for humanity, putting his entire project in serious jeopardy. His jibes may cause a moment’s pause, but he has Alyx and her father, our friends. We press on.

Once we reach the tip, we're captured and taken to Breen; amusingly, it’s a kind of self-inflicted capture, itself a sly comment on the player’s agency. But first, we’re greeted by Judith Mossman. It’s a curious exchange, perhaps easily forgotten but crucially important. “Don’t struggle, it’s no use,” she warns us. “Until you’re where he wants you there’s nothing you can do. I’m sorry, Gordon.” What kind of remark is that? A cursory reading of the line suggests she’s speaking of Breen. After all, we're currently in his clutches. But it doesn’t track. It’s not where we left Breen, who was begging us to stop. Indeed, one of the first things out of the man’s mouth is his amusement that we'd waltz right up to his office, given he'd spent so long hunting us. He’s as surprised by this rebellion as anyone.

So, Mossman could only be talking about one other character. How can that be? What is it that Mossman knows that we don’t? She called us a "puppet" before, didn't she? There’s that twinge of fear again. And just like that he's back, flaring in our memory with a cryptic smile and piercing eyes that seem to see through and beyond us. The perennial spectre overseeing our steps. What is it the G-Man wanted again? Why are we really here? Did he engineer this? No, no – we did this, not him. This is our story, our journey, our victory. And that’s the fear of the G-Man, right? The fear of having no control – the fear of being on-the-rails. But we're sure we aren't following his directive, because we're here to rescue Alyx. If we could see her once more, she'd quieten this unease and anchor us in place again - she'd reassure us of our place in this world, and thereby our freedom.

An argument as to humanity's ultimate fate has begun, as the opposing strands of science clash in old friends turned bitter enemies. Breen, failing to recruit Eli to his cause, resorts to cruder measures: Alyx is summoned as a bargaining chip. Upon seeing us, she appears crestfallen. It’s then we realise how many of her hopes she’d pinned on us. She's doesn't yet understand her own potential, her own importance. But then neither do we. Defiant to the end, she spits in Breen’s face when he mentions her mother. The old man’s stirred to anger, but he still thinks he holds all the cards. It doesn’t matter that Eli won’t capitulate and end the revolution.

It doesn’t matter, because “the Resistance has shown it is willing to accept a new leader. And this one has proven to be a fine pawn for those who control him.” He’s talking to us. “How about it, Doctor Freeman?” Breen grins. “Did you realise your contract was open to the highest bidder?” Our contract? The highest bidder? Pawn? Puppet! Eli’s cry of “No!” - there’s something behind that, something we cannot place. There’s that unease again, that unsettling feeling that all is not as we thought it was, opening our actions to doubt. Breen is finally the one to bring that doubt to the surface and shine a light on it. Before he can elaborate, Mossman turns on him, liberating Eli and Alyx and causing Breen to flee.

At long last we are reunited with Alyx. “Gordon, we haven’t known each other very long, but I know you didn’t have to do this. I had to rescue my father, but you – well, thanks for coming after me.” It’s an expression of gratitude that reaches us, and courses right back to the beginning, to remind us of a favour returned. She’s looking at us again, but her expression is very different to the one she bestowed us with at the beginning. It’s a look that suggests vulnerability, and a first step towards a willingness to be so. It's not lost on us that it's us she chooses to show this side of her. We realise in this moment that we've created a lasting, meaningful bond, one that roots us in this world and makes us truly feel part of it.

Let’s stop Breen - together.

True to form, the game doesn’t tell us how to defeat him, forcing us to make it up as we go along. We aren't able to weigh the consequences of our actions, because we're just making it up on the fly. He’s rising towards a portal that will take him to the Combine Overworld, and with him everything he’s learned about teleportation technology. We cannot let him get away. Hurtling through Combine troops, we manage to ascend the teleport reactor before him, and with a bit of Gravity Gun ingenuity – a tool Breen previously scoffed at – we close the portal. Breen falls as the reactor goes critical. Alyx, overjoyed, joins us on the platform.

We’re overjoyed, too. We did it. With the destruction of Breen’s portal we have at long last actualised the Resistance's liberation, and in doing so demonstrated our liberation. And then, at the precise moment you feel the most free, swept up in a powerful tide of emotions, an enormous explosion blossoms out of the reactor. Its force will consume us. We’d think it was over, if we had time to react.

Well, time is exactly what we have. It freezes. A sinister voice reaches us, both everywhere and nowhere. The G-Man steps forward, and in a single stroke dashes our dreams of liberation against the rocks. They were only ever dreams, really. Manufactured by a series of events masquerading as coincidences. We were never free. We were always a pawn – a pawn in a cosmic war. We don’t know what it was about that explosion that our employer considered satisfactory – an apparent job well done – but it did the trick, and it’s time to take us away. Back to the cold stasis. Back to a dreamless sleep and a world without time, consequence, or thought.

And Alyx? That young woman who saved our life, and whose life we saved in turn? She’s left frozen in time, the explosion inches from annihilating her. She’s everything we’ve come to care about, and now she’s receding into a blur, the G-Man sparing her only a casual, fleeting gesture. It was only a dream we’d been living, imagining ourselves part of a tightly knit group of scientific revolutionaries who had succeeded in striking a blow against an interdimensional empire.

We desperately don’t want Alyx to die. We want to save her again. But we can’t.

We’re alone.

That right there is the spell HL2 weaves: its sense of freedom comes not from being able to choose between paths, but from opening the door to allowing us to give a damn about an NPC in a raw, visceral way, thereby making us feel part of its world. So much that when the ride stops, the last thing we want to do is get off. It’s interested in agency and causality, and it explores them in its players’ relationship with its characters. Alyx Vance is precisely what makes it all work. She’s the through line to all of these events - the empathetic core of Valve’s endeavour who allows you to invest heart and soul in this world beset by a cosmic evil to whom you opened the door. The cruelty of leaving Alyx's fate uncertain is a stroke of genius, really. The game's confident its spell was a success, and it's right to be.

I think Dark Energy, then – a fun title, ironically deployed as both the world expands ever more, glimpsed through the Combine portal, and contracts as we’re removed from the board – is the strongest ending in the series as it’s a proper conclusion to the game’s thematic purpose. You don’t see that a lot in games! Half-Life 2 not only fulfils what it sets out to do, but marshals all of its strengths in service of that end. It’s an ending that was derided as an empty cliffhanger, but that couldn’t be farther from the truth.

It is an ending that is uniquely Half-Life, ambiguous and cryptic, but superior to the original’s by virtue of the infinite value of empathy, symbolised in the player’s relationship to one Alyx Vance. It's an ending that succeeds by virtue of making you care, whilst challenging the strictures of linearity in game design. I fear that sounds a little abstract, but I hope I've managed to at least demonstrate how intimately connected the two really are. I suppose if you wanted to take the reading further, and many have, the G-Man's something of a metaphor for Valve / the game designer. They're the ones orchestrating your path, ensuring you see what you need to see, shepherding you to a desired end and possessing the ability to extract you from the action whenever they please. The trick is to create the feeling that players are organically developing the action according to their own agency, but outside of individual gameplay encounters it's fundamentally all predetermined. Bit like how the G-Man operates. The difference is that the G-Man doesn't give a damn about whatever it is you've come to care about, whereas Valve spend the entire game stoking the tension between players' investment and a preset journey, because they do care.

All so that they can build to a crescendo where they take it all away.

The episodic games don’t quite have the same bite, arguably serving the mechanics of plot more than preceding entries, but Episode Two is a game built on emotion, connectivity, and empathy perhaps more than any other. In what might be one of the most significant developments in the series, Episode Two starts with the vortigaunts performing the extraordinary act of entangling our vortessence/soul with Alyx’s. It’s an act completely rooted in the game’s immersive purposes, running counter to the isolation and loneliness of Half-Life 2’s closing scene (there's definitely much more to say on that moment in light of everything I've covered, but I'm conscious of having already gone on (and on) quite a bit...). We literally cannot be taken from her again.

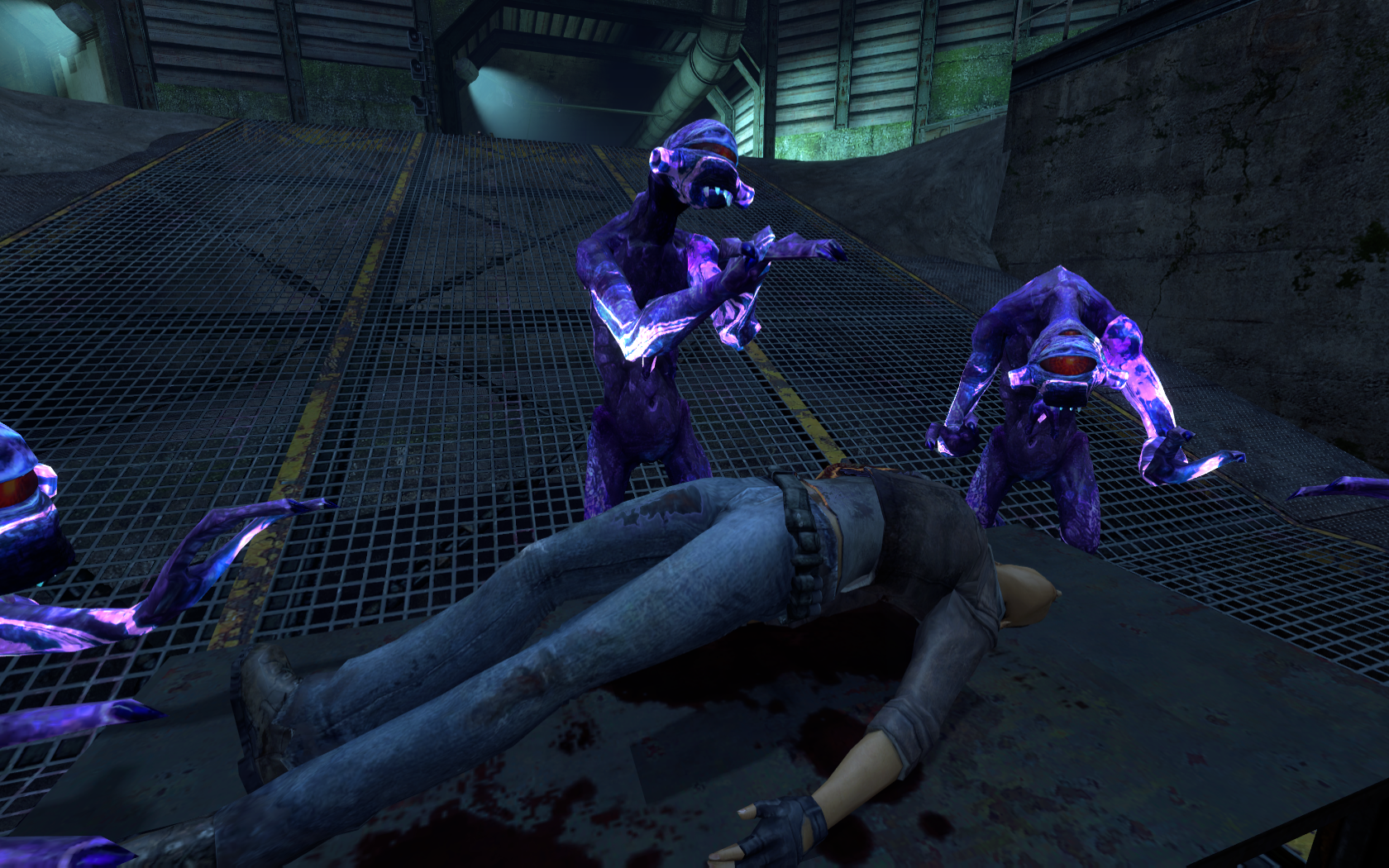

It might be that Episode Two’s ending is the ultimate test of the player’s commitment to the world, the logic of empathy taken to its natural conclusion: mourning the murder of Eli Vance at the hands (or tongues) of the Shu’ulathoi. In that ending, we’re not cruelly removed from the action, but left powerless to defend Alyx and her father, and finally immobile in futility as Alyx weeps over his corpse. We can’t reverse this – we can’t prevent the loss of the one thing Alyx held most dear. We care about Eli Vance, but we care about Alyx Vance even more. From the moment Alyx leans over us for the first time, we were always building to an emotional climax in which her grief became our grief. If anything is proof of Half-Life 2's success, it's this.

I don’t know where Half-Life: Alyx is going or what it has in store. I don’t know what playing as Alyx is even going to be like, but it’s definitely an experience I want to have, precisely because she’s not Gordon Freeman. There’s so much she can be that Gordon can’t, and the narrative possibilities are incredibly exciting. We go into it with a well of empathy for this wonderful character.

It’s a prequel, set some time in the near past. I suspect, though, that memory of the future will have more than a passing role to play.

Thanks for reading.