DISCLAIMER: parts of this post were originally written in the summer of 2016 for Pipedream Comics, but they didn’t end up running with the finished piece. At the time, Steam Greenlight still existed, and I talked more extensively about the pros and cons of that now defunct service. In light of the recent closure, I’ve repurposed the piece to look more carefully – although still somewhat cursorily – at Steam as a platform for comics.

At the end of February 2016, we chose to launch the comic on Steam Greenlight. If you’re unfamiliar with Greenlight, it was a subsection of Valve’s digital distribution platform Steam that allowed content producers to submit their products for a small fee (a one-off payment that was donated to the charity Child’s Play) and open it up to public voting, which was a kind of glorified and often arbitrary popularity contest. On the basis of your premise and the relevant media required to submit the product, Steam users were then able to vote on whether or not they would like to see your product on Steam. And then, after an indeterminate period, inexplicably and often without knowing why, you were greenlit! Yay! This secured you a place on the much-coveted Steam catalogue.

If not, you could stick around indefinitely to pick up the momentum and exposure you needed to reach the finish line.

Greenlight was quickly inundated with titles, and though flawed, it was a great avenue for small teams and indie developers to showcase their work. Valve’s reasoning was clear: they (Valve) did not have enough confidence in themselves to act as gatekeepers to what does and does not appear on Steam. At some point, Valve recognised they were not able to accurately determine which titles would be of interest to customers. Last year’s Stardew Valley is an oft-cited example of a title whose enormous popularity Valve could not have predicted.

So, as in all their decisions, it was ultimately driven by a desire to empower customers. What do you want to see on Steam? In stepping away from the process, Valve took the belief that the best products would naturally bubble to the surface, whilst constantly fine-tuning and reiterating their Recommendations Engine on the Store Page. Valve’s ethos is laudable, and has arguably been instrumental in making Steam the industry titan it is today. It is, however, not an ethos without its own fair share of problems, and Greenlight was a good example of that.

Red light! Green light! There was no "red light"...I just wanted a picture of my boy Tom Cruise

The titles submitted to Greenlight were almost exclusively video games, which is no surprise given that Steam established itself first and foremost as a platform for distributing digital copies of Valve’s own games, and, eventually, the products of some of the biggest publishers in the world.

But we did not submit a video game. We submitted a digital comic. And we were Greenlit in two weeks. To say we went into it unprepared is an understatement. Our product was a comic, but all of the specifications for Steam were tailored to games! For instance, a requirement for any project on Steam is that it must have at least one video. So, we had to put together a trailer, complete with a musical track in the vein of Half-Life’s electronic ambient score, and clearly and effectively convey to users that yes, this is a comic, and not a video game. And that’s when things got tricky. Whilst we are by no means the first digital comic on Steam, we are, as of writing, the first stand-alone digital comic (the rest, outside of visual novels – a whole other super successful medium – were tied to games, as I’ll get into). To say this caused some confusion amongst Steam users is, again, something of an understatement.

The first thing we had to figure out how we wanted to display the comic. Steam’s not built for comics, so it doesn’t have its own display features. Outside of depositing a PDF in users’ Steam directories (which we were very reluctant to do so, in spite of some pressure from customers), we’d have to build the necessary tools ourselves. So, Mike built an app – a kind of hub from which you can read the comic, access bonus features, and have as much control over your reading experience as you would with a PDF or a title on ComiXology.

One of the in-screen menus for A Place in the West

When it came to deciding upon how to present the comic in the app, we thought it best to mimic the dynamic, animated menus of Half-Life 2. We commissioned a map featuring one of the comic’s most ambiguous figures, our bioluminescent, tentacled ‘Ubdisha’. We then added a menu, replacing “New Game” with “Start Reading”, a language option, and so on. Although we explicitly stated that A Place in the West was not a game, it was clear some people found this kind of imagery misleading, which was not our intention – just one of many obstacles we encountered in simply trying to convey the idea of a ‘comic on Steam’. It is completely possible – and somewhat disconcerting! – that many of the people who voted ‘yes’ believed they were going to receive a game, and not a comic. Some suggested we may even be sued for the use of Valve’s intellectual property, even though we were releasing the first chapter for free!

So, what made Steam the platform for us? The first answer is the most obvious: it’s the hub for all things Half-Life and Valve, and if we were going to find a receptive audience anywhere, it was going to be here. And in lieu of any new Half-Life game, we thought fans might appreciate new content in one of their favourite universes, canonical or not. But the biggest reason was Steam itself. Recently, ComiXology has become the go-to hub for digital comics, unmatched by its rivals and offering a truly excellent platform for reading the latest and best comics (Image! Dark Horse!) at a reasonable, affordable price. There have been murmurings from within Valve about Steam embracing comics more broadly, but that hasn’t amounted to very much as yet.

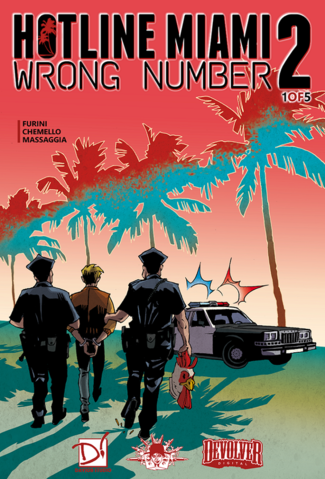

As already stated, Steam is not without its share of “comics”, but they fall into two distinct categories. You have the “visual novels”, which combine interaction, animation, audio, etc. – such titles, for example, include the Sakura series and Cyber City 2157: The Visual Novel (there’s a noticeable trend towards anime-style productions in this area, and they are enormously popular), and comics that come attached to video game titles. Hotline Miami 2 and the now likely cancelled Blues and Bullets are two very prominent titles that stick out. The latter title is likewise an interactive feature, but includes traditional comic book panelling unlike some of the visual novels.

Probably never to be seen again

As of writing, the digital comic component of Blues and Bullets has three reviews (it was four when I first wrote the article!), and it was released in July 2015. That’s not a lot, but our feelings are such that the lack of reception is that it’s simply an ancillary component to the larger product, and thus arguably going to attract less attention. Hotline Miami 2’s digital comic is a different thing altogether, and it’s all the better for it. Illustrated by an Italian comic book company called Dayjob Studios, the comic is launched via an app built into Steam and found within the “software” section of your library. Its neon-drenched menu is animated, and you’re able to select ‘issues’ off a table strewn with an assortment of weapons and other paraphernalia. Once an issue has been selected, you can flick between the black-and-white pages at your leisure. It’s simple. It works. And it’s very much in the style of the game to which it owes its title.

Hotline Miami 2

It boasts more reviews than Blues and Bullets, but its negative reviews touch on some of the problems we encountered, too. Chiefly, should Steam even allow comics to be part of its service? Is it acceptable to purchase and read comics on Steam via an app, or is that straying too far from its original ‘purpose’? We were taken aback by the sheer number of Steam users who were outright against the idea (unless they were components to games, which could be said of A Place in the West and its unsanctioned relationship to the franchise, but that’s tenuous at best). This struck us as backwards thinking, and demonstrative of the entrenched attitude of those who dislike change, or see additional mediums as an infringement upon their own perception of the platform (which is ironic given the internal debates as to what even constitutes a video game, which you see over things like Firewatch...which is an odd debate, because of course Firewatch is very much a game).

Yep, definitely a game.

But Steam belongs to Valve, and every step of the way they have been open about broadening the platform’s horizons to include new mediums. A simple example of this is not just the growth of software available on Steam (Design & Illustration, Video Editing Tools, to name but two of what is surely hundreds), but the addition of film and television. That trend is only set to grow; you can download soundtracks to your favourite games, watch movies, dabble in video editing software and, with APW, read comics in your Steam library. We certainly understand and acknowledge those who decry the saturation of Steam with new mediums, but it is very unlikely comics, or any other product, are going to take precedence over the enormous assortment of games already available – and the video game well is never, ever going to run dry as Steam, and gaming, move into the future. If Steam can accommodate games and films, there’s simply no reason why comics can’t follow suit and be as equally successful.

Which brings me to my final point, and something I hope is a bit of a conversation starter.

Oh, this is better

When Mike and I spoke with Valve at Steam Dev Days in Seattle last October, they hinted that Greenlight was on its way out. As it transpires, that replacement was to be Steam Direct, which went live last month. Steam Direct does away with the voting system altogether. For a fee of $100 (recoupable by developers should their game pass $1,000 in revenue), anyone can submit their game to Steam and see it approved. It's worth noting that the original $100 fee for Greenlight got you in for life - there was no upper-limit on how many games you could submit. With Steam Direct, it's $100 per game. But given this is recoupable, it roughly balances out.

There is little doubt, at least in my mind, that Steam Direct is a vastly superior system to Greenlight. In keeping with Valve’s ethos, it removes an arbitrary hurdle (a wonky democratic process) between creators and the store page. That said, Mike and I don’t actually agree on the fundamentals of Steam Direct. Mike believes, with some justification, that the low-cost threshold will unleash a deluge of shitty products that will bury smaller, more talented developers. Whilst I think there’s merit in Mike’s argument, I’m of the opinion that barriers put in place to regulate content, such as a higher entry cost, are more dangerous, as it risks completely shutting out developers, robbing them of any chance at all.

Whilst it’d be nice to see some kind of quality control, what would that look like, and how does it discriminate? Valve chose the lesser of two evils.

The significant thing for us in all of this is that with just $100, you can put your product on Steam. So, thinking back over this whole post, the question of whether or not your comic belongs on Steam is no longer a question for the Greenlight community. It’s a question for you.

It is our belief that Steam can absolutely be a successful digital distributor of comics. But in order to do that, we need more titles on there, more diversity, more choice. We chose Steam because it made sense to us as a video game tie-in, and while we haven’t been an overnight success, we have built up a base of readers and there is a noticeable interest in comics and what they can offer. We feel more confident in ourselves as a comic book now, and subsequently less dependent on the Half-Life facet of our project. In light of this, Mike has initiated a series of significant changes to our app: controller support, audio functions, more translations, commentary tracks, and more. We don’t necessarily have a timetable for any of these things, but they are being worked on as we speak.

I’m going to go into this more thoroughly in a follow-up post, but you can probably see where I’m leading you to(!). We don’t know when Valve are going to implement a system that allows Steam to display comics. It could be tomorrow, next week, next year, or simply never at all. There's no way to tell at this stage. If Valve were to implement such a system, it may make our app redundant, and in such an event we will adjust accordingly. But we will continue to work on and improve our app, with the aim of making it a vital part of our product.

But the time has come for us to consider making our app available to other comic book creators, and tailoring it to their needs. So, if you want to put your comic on Steam but are unsure how, get in touch – we think we can help!